1 novembre 2015 / 12 h 14 / Magie du bol tibétain chantant et de la pizza

Les magasins Nature et Découvertes sont formels : “Héritier de l’Âge de Bronze, ce bel objet traditionnel du Tibet est entouré de mystère. Le frottement du maillet en bois sur les parois martelées de ce bol chantant fait naître un son unique. Vibrant d’une belle intensité, il favorise l’inspiration, la détente et la méditation. Selon une légende tibétaine, ce bol chantant est composé d’un alliage subtil de sept métaux, liés chacun à un astre.”

Ce qui est sûr, c’est que cet objet qui n’a rien de traditionnel, est bel et bien entouré de mystères savamment entretenus.

L’invention des “bols tibétains qui chantent” remonte aux années 1960-70 et est probablement d’origine nord-américaine. Auparavant, le bol tibétain servait… de bol, mais pas encore à vriller les tympans. Aujourd’hui, il est devenu un article indispensable de tout bon “tourist trap” népalais et un outil incontournable de tout guérisseur chamanique-nouvel-âge qui veut t’ouvrir bien grand autant tes chakras que ton portefeuille.

(Selon la légende de la pacotille, “ce bol chantant est composé d’un alliage subtil de sept métaux, liés chacun à un astre.” Sachant que le mercure et le plomb sont censés figurer parmi ces sept métaux, évitez de l’utiliser comme un vrai bol… ses effets risqueraient d’être autres que psychologiques.)

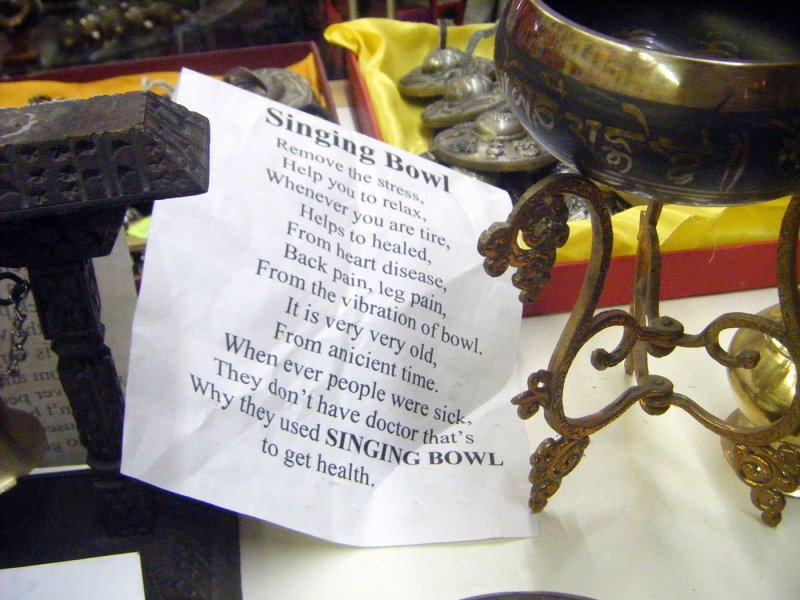

“Singing bowl from anicient time, very very old, $$$.” Heals all diseases except stupidity.

[Photo Bradley Gordon.]

As it turns out though, singing bowls’ supposed antiquity and Tibetan-ness is rather contentious. Academic consensus is that the ‘Tibetan’ singing bowl is a thoroughly modern and Western invention, and that singing bowls are really not Tibetan at all. Perhaps the easiest way to appreciate this (…) is by noting that while there is indeed a Tibetan term for both standing and hand-held prayer wheels (maNi ‘khor lo/lag ‘khor) no specific term for ‘singing bowl’ exists in Tibetan. […]

Singing bowl enthusiasts typically state that the bowls are shrouded in secrecy. It is not ucommon for them to acknowledge that (as is in fact the case) no written records exist for the bowls’ use and that Tibetans deny doing anything with metal bowls other than putting stuff in or eating out of them. Authors often recount how they have tried – sometimes for years – to elicit further information about the bowls’ history and use from Tibetans. Tibetans’ silence or disavowals of knowledge are interpreted in three typical ways: 1) the Tibetans to which the author spoke were not privy to the deepest secrets of their own culture, and therefore unable or unqualified to speak 2) These Tibetans had forgot or lost the secret knowledge of which the bowls are a part or 3) These Tibetans are hiding something, guarding their knowledge from prying outsiders or for fear of persecution by ‘orthodox’ Buddhist authorities. The bowls’ physical ubiquity, their self-evident ordinariness thus contrasts with the depth and opaqueness of the secret histories and science that they are supposed to embody. Singing bowl enthusiasts seem unwilling to allow for the possibility that singing bowls’ resonant properties are incidental. The absence of credible information or proof of the bowls’ use in Tibet only goes to confirm for them the incredible secrecy and integrity of the ancient oral tradition that they insist lies behind the bowls’ mundane exterior. […]

It’s thus possible that using metallic Himalayan bowls as musical instruments for broadly ‘spiritual’ purposes originated as recently as the late 60s or early 70s. In 1969 two American musicians by the name of Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings travelled to Nepal, where they interacted with Tibetan refugees and studied with lamas from the Kagyu lineage living in exile. During this time the two became fascinated by traditional Tibetan musical instruments, and began experimenting with playing them in both traditional and non-traditional ways. In 1972 in London they released the first of what would become a series of albums that show-cased their efforts. ‘Tibetan Bells’ featured seven entirely electronically un-altered tracks that combined the sound of Tibetan dril bu, gongs (rgya rnga) and ting shag (finger cymbals) with tones produced by striking and rubbing metal bowls. […]

Another exile Tibetan blogger, the anonymous ‘Angry Tibetan Girl’ weighed in too, to note that singing bowls “were never a Tibetan thing” but were “an invention by Newari merchants” intended to be sold to ‘fascinated’ white orientalists. “Now Tibetans sell’m too, orientalism sucks, its slathered on us without our choice, but who said we can’t gain a little from it”? […]

Around the same time that the singing bowl industry was taking off, and more bowls with more elaborate painted and engraved Buddhist icons and mantras were emerging in South Asian markets, Austrian anthropologist and practitioner of Hindu tantra Agehananda Bharati coined a term that is useful for understanding singing bowls’ status today. To make sense of the existence and popularity of modern, ‘Western’ forms of yoga in India, Bharati pointed to what he called a ‘pizza effect’. Here, cultural phenomena that are initially from one place get transformed or embraced in another only to be re-imported back to their source-culture or context. Bharati based his term on a particular reading of the modern pizza: Italian immigrants to the United States re-invent a low-status or banal food from their homeland, thereby imbuing it with an appealing, ethnic charisma. This culinary novelty is then re-imported to Italy where it is incorporated and potentially embellished even further so as to seem more ‘authentic’ (chefs in Rome swear ‘the original real Italian pizza’ always used a thin base and lots of rosemary etc). As the pizza analogy demonstrates, these sorts of complicated cross-fertilizations and ‘hermeneutic feedback loops’ as Stephen Jenkins has put it, are potentially endless. While five hundred years ago Indian yoga may have been more about corpse-ash and skull-cups than about Lulu Lemon and coconut water, and while today’s ‘ancient yoga’ may have been a more modern construction forged through collaborations between Indian holy men, nationalists, and ‘fascinated’ colonialists, it remains that native Indians today are selling yoga back to the West, and practicing it themselves. […]

Savage Minds, Ben Joffe: “Tripping On Good Vibrations: Cultural Commodification and Tibetan Singing Bowls.”

1. Le 2 novembre 2015,

Karl, La Grange

C’est un peu comme le HTML5 du bol tibétain.

2. Le 7 novembre 2015,

Marie-Aude

ça ne guérit manifestement pas de la mauvaise orthographe :)